Beeping. Clanging. Hammering. Drilling. Many surgeries—especially orthopedic and neurologic procedures—produce hazardous noise levels in operating rooms that negatively affect the well-being of staff as well as their job performance and patient outcomes.

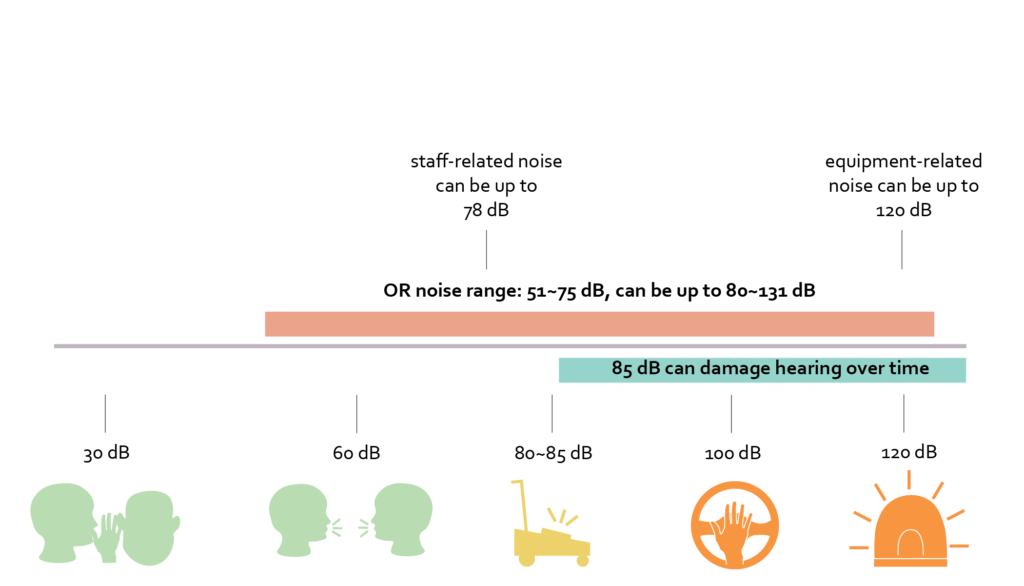

Lately, there’s been a lot of “noise” about noise in hospitals, with studies showing that noise levels in a hospital OR can reach up to 120 decibels—the equivalent of a siren or a loud rock concert. This stems from both equipment-related and staff-related noise that reverberates in the OR due to hard, impervious surfaces used for infection prevention that reflect sound.

Because exposure to 85 dBs and up over time can damage hearing, regular workers in ORs are reporting noise-related hearing loss. Substantial hearing loss has been demonstrated among anesthesiologists.

In a study conducted by Mark S. Wallace et al, 66% of anesthesiologists had abnormal audiograms, and those younger than 55 had a hearing acuity significantly worse than the general population.

I have family members who are surgeons and are among the regular OR workers experiencing noise-related hearing loss. Because of this personal connection, as a healthcare designer, I felt compelled to learn more about acoustics in the OR environment and explore opportunities to alleviate ambient background noise in this setting.

This led me to work with my colleague In-San Chiang, a NOMA Research Fellow, on an in-depth Systematic Literature Review to study existing research articles about OR acoustics and their impact on staff performance. In this blog post, I take a closer look at the study and how it shed light on future research opportunities.

In Search of Solutions

There have been numerous studies validating the need for noise reduction in operating rooms. These studies have ranged from exterior factors, including suite location, as well as interior procedure room factors such as room layout, equipment, and staff behavior. However, best practice operating room design addressing noise in the OR has yet to be established. Why? Because it’s hard to quantify.

Operating room noise simply isn’t the same for every procedure, and there are a number of variables we don’t have control over. For example, the type of equipment used in the OR, the number of staff in the room (as well as their volume levels), and even the music some surgeons like to listen to while performing a procedure.

For this reason, we set out to evaluate multiple scenarios that we could quantify and develop design solutions that will result in a measurable reduction in noise intensity in the OR.

For our literature review, we chose to use both empirical and non-empirical peer-review journals published between 2000 to 2020, and used PubMed as our main database. Relevant articles from Google Scholar and some “snowballing” were also included.

Our findings detailed in the study show that with an increase in noise, there is a corresponding increase in staff stress and anxiety levels. Moreover, speech becomes less intelligible, resulting in both inefficiencies and distraction. Hard wall surfaces in the OR exacerbate the impact of ambient noise, resulting in staff hearing loss and an increase in medical errors.

Previous interventions have included the impact various room sizes and equipment placement have on reverberation time, the introduction of both white and pink noise, music and its influence on cognitive task performance, and the enforcement of the “sterile cockpit” rule (that mandates an environment free of unnecessary distractions) at critical points during the surgical procedure.

Implications for Practice

It probably goes without saying that improving OR acoustics will require the elimination/mitigation of noise-producing offenders. Along with equipment and staff, the most significant of these is room design. External factors include suite location; procedure room location within the suite; adjacency to vibration-producing spaces/mechanical rooms; ductwork; and storage location.

Internal factors comprise room size; wall and ceiling configuration; room layout; storage; surface materials; staff interactions; staff circulation; equipment location; HVAC; and something I personally never considered before—door location.

Our research revealed an analysis by Young and O’Regan that determined during an average cardiac procedure, staff goes in and out of an operating room over 90 times per case, which equates to over 19 times an hour. Think about the noise impact of a door opening and closing 19 times an hour coupled with other acoustic stressors!

Ultimately, our baseline investigation gave us an all-important understanding of the current state of acoustics in the operating room environment, which is outlined in the literature review. Based on our findings, we determined numerous next steps for future research opportunities. These included:

- Interviews with medical staff to understand their perception of noise levels in the OR

- Measuring staff stress using heart-rate data from wearable technology

- Measurement of existing reverberant conditions within the OR

- Measurement of existing sound levels within the OR

- Evaluating the procedure room layout

- Evaluating the proximity of supplies

- Examining door types and location

- Studying staff and supply circulation patterns

- Evaluating procedure room HVAC

- Observing staff behavior

The Desire to Make a Difference

Recently, we embarked on one of these research opportunities with UF Health North (UFHN) in Jacksonville, Florida, in which our Healthcare Research & Innovation team partnered with an acoustical consultant to take measurements of the existing reverberant conditions and sound levels within their ORs.

Through research projects like this, our desire is to make a difference in the lives of regular OR workers—people like my sister who suffer from noise-induced occupational hearing loss—by determining the best design configuration for an OR so it will provide the optimal acoustical performance.

Based on our research, design implications to support this may include using sound-absorbing materials with infection prevention capability on OR walls and ceilings, as well as assessing room size, configuration, and equipment placement to reduce reverberation time.

As architectural teams work toward the design of the operating room, it is critical they understand the noise implications of design decisions as well as potential opportunities for acoustical improvement.

Ultimately, it is our hope that our research will help to expand these opportunities and lead to an improved quality of life for those who spend their days, months, and oftentimes years working in the OR environment.