After spending seven years as a nurse technician in the emergency room at Moses Cone Hospital in Greensboro, North Carolina, Lakiesha Stanley, a Healthcare interior designer based in Gresham Smith’s Charlotte, North Carolina office, was drawn to the idea of saving lives on a broader scale. Driven to create spaces in which she could impact more than one patient’s life at a time, Lakiesha set her sights on a career as an interior designer in the healthcare realm.

While studying interior design at the University of North Carolina Greensboro (UNCG), she was struck by the lack of diversity in the curriculum as it related to people of color. After graduating from UNCG, the former health professional turned interior designer journeyed to Hawaii where she was introduced to a “Hawaiian sense of place” in which culturally-based design was actually celebrated. She learned that cues from Hawaii’s past not only dictated physical forms of design in the Aloha State, but also helped to inspire and educate.

When she returned to the U.S. mainland, Lakiesha was reminded that the subject of cultural sensitivity and inclusion in the practice of design rarely—if ever—came up. Motivated by this lack of diversity in design, she posed a question to her former college professor at UNCG, Laura Cole, now an Assistant Professor of Architectural Studies at the University of Missouri (Mizzou): “How do you feel about being part of an RFP for grant funding that’s centered around a racial literacy curriculum?” Professor Cole’s response was immediate: “Let’s make that conversation happen!”

Although the RFP didn’t pan out at the time, Lakiesha partnered with Professor Cole to develop a modified version of the curriculum that the professor introduced to her Interior Design Studio IV class as part of the spring 2022 syllabus at Mizzou. Her students were tasked with creating the conceptual design for a freestanding birth center aimed at serving the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) community of Columbia, Missouri.

The speculative location identified for the project was a circa 1980s two-story building situated directly adjacent to a historic Black neighborhood on the north side of downtown Columbia. The students’ more specific challenge? To deliver original design solutions for the birth center based on their understanding of cultural context, design fundamentals, building systems, code compliance, human-centered design, and sustainable design principles. We recently caught up with Lakiesha to learn more about this unique design curriculum and project.

The students in Professor Cole’s class had just one semester to come up with design solutions for a freestanding birth center for the BIPOC community in Columbia, Missouri. Why a birth center?

Lakiesha Stanley: Historically, people of color have not been treated well at hospitals. Even today, Black mothers in the U.S. are four times more likely to die from maternity-related complications than white women. Because of these negative experiences, BIPOC mothers are looking for birth alternatives, which has led to a rise in the popularity of giving natural birth at a birth center. As Columbia only has one natural birth center, which is at its Women’s Hospital, our project sought to fill that gap. The main goal was to provide BIPOC moms with a safe place to give natural birth that will make them feel both nurtured and welcome.

Why do you think the work of Black designers hasn’t found a home in mainstream interior design, and how does this project help shine a light on that?

Lakiesha: I think the void of African-American perspective in interior design suggests that the African-American experience belongs to a subgroup of Americans. And that totally obscures the fact that the history belongs to all of us. This project brings the Black experience into the design classroom and helps illuminate racial injustice for design students. It also adopts the lens of human well-being as a healing path forward, which I think is equally as important.

In terms of racial diversity or lack thereof, there aren’t a lot of African Americans in the design spectrum as a whole. In fact, only 2% of licensed architects in the United States are Black according to the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards.

Oftentimes, I’m the only African-American designer on a project, and this disparity got me thinking: Do we not design for African Americans because our voices aren’t in that space to begin with? How can you design for diversity, equity and inclusion if your voice isn’t there? Sans the influence of the African-American culture, the design conversation merely centers around what you think a space should be.

Tell us about the class and how did you and Professor Cole prepare the students to take on such a unique project?

Lakiesha: The Design Studio IV class was a mixture of architecture and interior design students. As it turned out, it was an all-female class. Only one of the 15 students was African American, and Professor Cole shared with me that this student didn’t initially feel she had a voice in the class. However, the other students were constantly asking for her input on the project, which really made her open up. It was exciting to see.

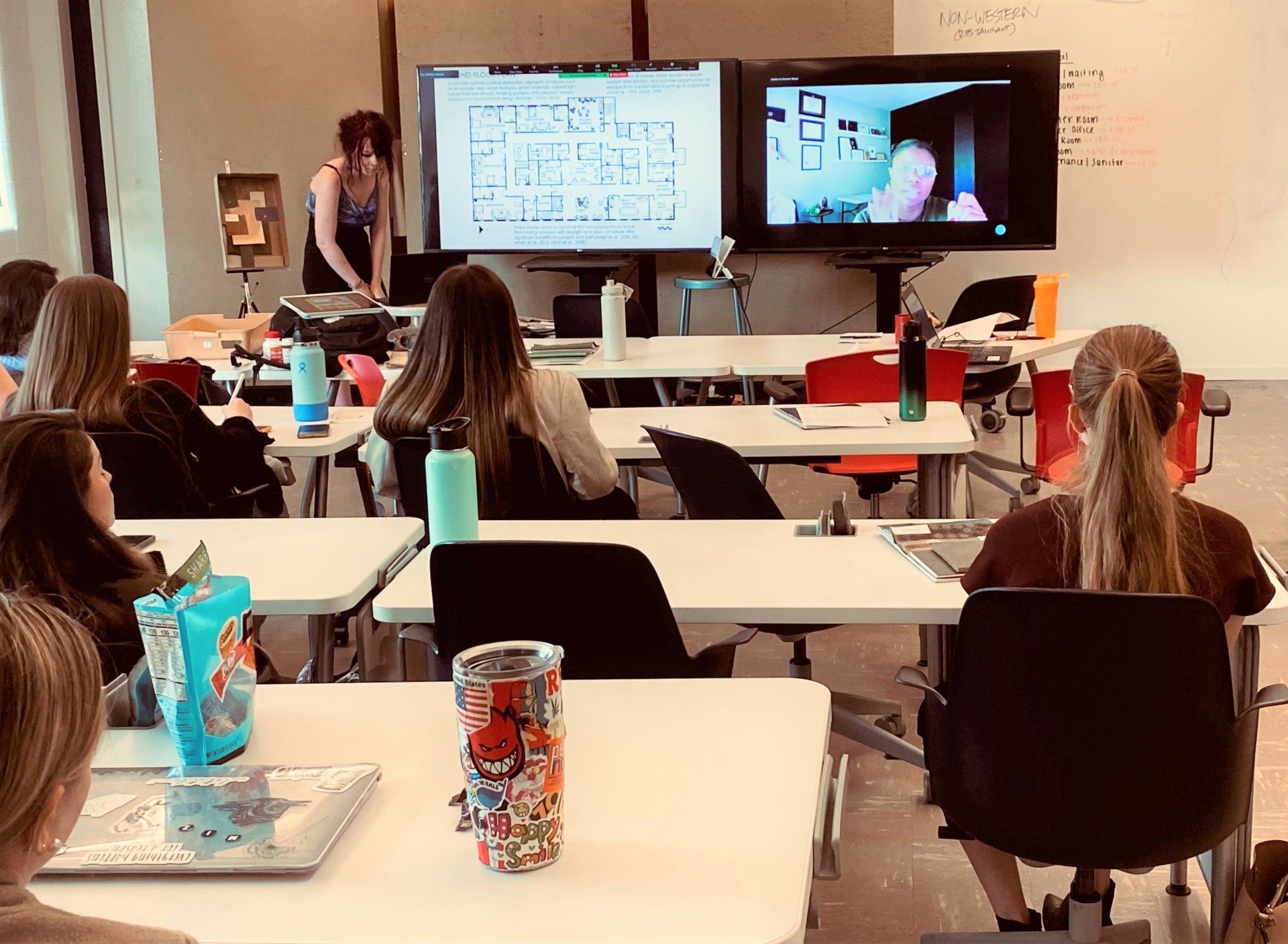

In terms of preparation, we brought in panelists, including professors and design and healthcare professionals, who shared their unique perspectives with the students. The nurse practitioners and midwives, for example, were able to talk about what their clients liked and disliked in a space, and the students really blossomed into an understanding of what was needed in a birth center.

Professor Cole also put out a call to anyone and everyone who had gone through the birthing experience—even if they’d lost a baby. This gave the students the opportunity to interview African-American women who had gone through both childbirth and child loss and were able to provide a firsthand account of their own birthing experiences. From there, we began the process of determining exactly what the space needed to be.

The first phase of the project involved a deep dive into evidence-based design readings along with extensive programming and predesign activities. For example, we gave the students a list of space needs for a 3,000 to 4,000-square-foot birth center within the two-story building, which included a ground-floor lobby, a second-floor lobby, three to six birth rooms—which were the central consideration of their design—as well as exam rooms, a family lounge, one to two nurse stations, a children’s area and other key program elements. We also invited students to add their own unique twists to the list of space needs.

Ultimately, the sharing of experiences and perspectives at the beginning of the semester not only helped the class integrate concepts such as color palettes, space plans and textile designs into their concepts, but also got the students thinking more about the meaning of cultural sensitivity and how their designs could support both diversity and inclusion.

What was your role in the classes and what has been a highlight for you?

Lakiesha: I served as both a critiquer and an interviewer for the students. I especially found the critique sessions inspiring as they gave each student a chance to speak about their design concept’s evolution—how they went from zero to 100 with the project, and how their design could benefit the client, patients and family members.

A personal highlight has been seeing others get behind an idea that started out as a “coffee conversation” about equity, social justice and inclusion in the design curriculum. One of those people is our client, Tanya Smith-Johnson, a certified professional midwife (CPM) and president of the National College of Midwifery. Tanya served as the concept owner of the building in downtown Columbia. Her overarching goal is to serve the BIPOC community in Central Missouri with an affordable natural childbirth option. The students’ design concepts have helped breathe life into that vision.

Tell us about some of their design solutions.

Lakiesha: The class really took the time to think about the BIPOC community, especially the African-American culture and its relation to maternal healthcare. For example, one of the students reimagined the front door to the birthing suite experience due to her studies about how important the “porch” experience is to the African American culture—it represents an opportunity to unite, celebrate, and welcome people into their homes.

What’s Next?

Lakiesha: Now the students have given their final presentations and the spring semester is over, we want to continue the conversation. Our hope is for this design curriculum to become CIDA-accredited as well as introduced to architecture students. Why should it just stop at interior design? After all, architects design the building, so why shouldn’t they also design for cultural sensitivity? In fact, Matt Harrell, an architect and a Market Vice President for our Healthcare division, probably summed it up best when he recently said: “You cannot have design without understanding the culture of your clients and the end-users.” I thought that was a clear and beautiful understanding.