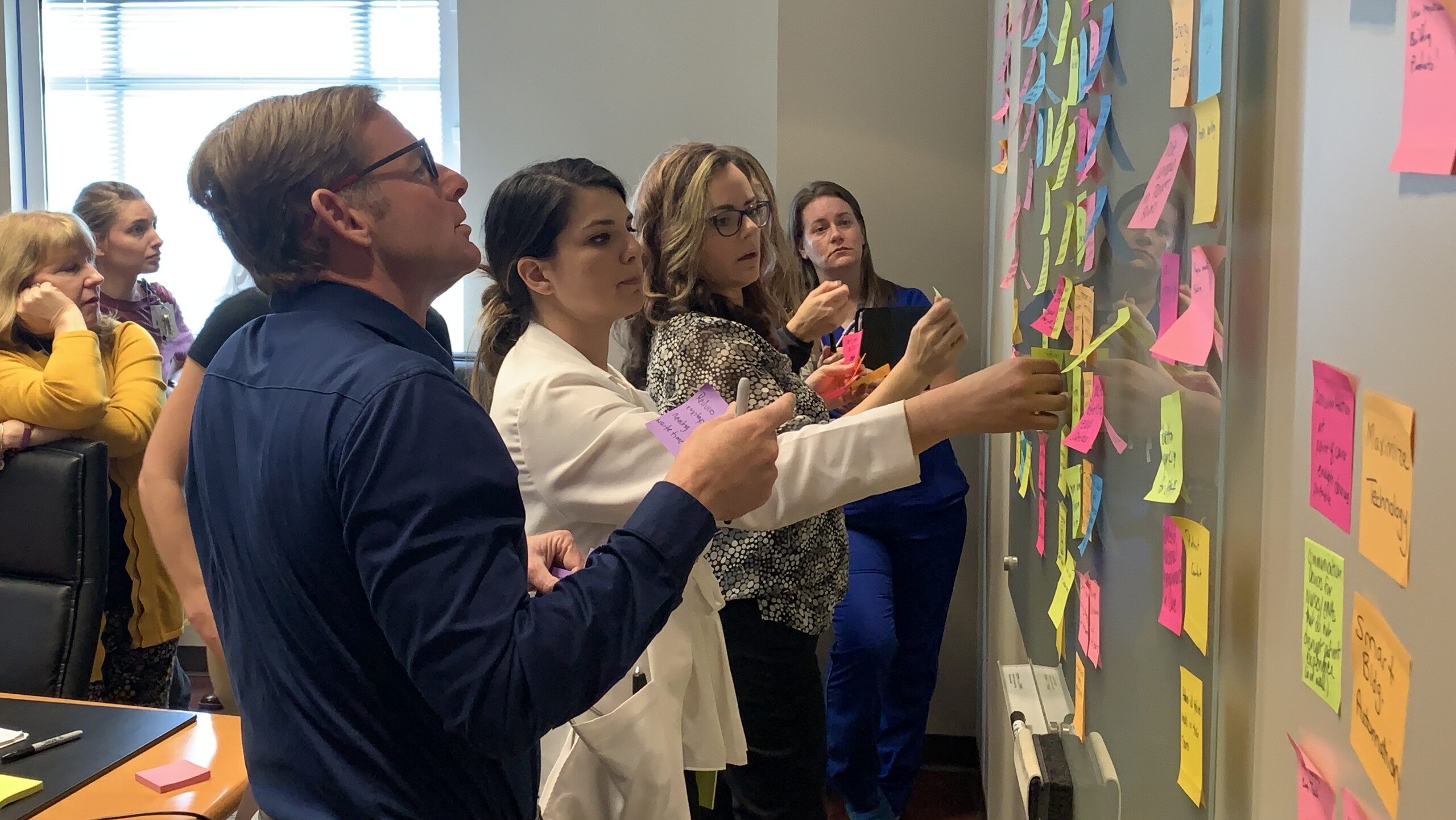

More than just a slew of Post-it notes, Design Thinking is a well-known iterative process centered on stakeholder feedback from a co-design team made up of clients and designers. At Gresham Smith, our Healthcare group has been using Design Thinking as an effective tool essential to the evidence-based design approach.

As a research method that is primarily qualitative, Design Thinking enables teams to collect data through direct observation, focus groups and interviews, as well as other means. It is particularly useful during the predesign phase of a project and is valuable throughout all phases of the healthcare design process.

Design Thinking also aligns well with Lean methodologies. Why? When executed effectively, it is very efficient in its use of our most valuable commodity—time.

Specifically crafted around a targeted goal, Design Thinking is not only engaging for the client but also allows us to gather a large amount of insightful information that is useful for the co-design team.

In this post, we take a deep dive into how our Healthcare group uses Design Thinking as a research method to determine how healthcare environments can be enhanced to improve outcomes for staff and patients alike.

Our Visioning Process

Evidence-based design is centered around the framework of evidence-based medicine and integrates empirical research into the design process. Design Thinking falls under both research and innovation, and is a critical component from the very beginning of a project and throughout the entire design process.

Integrating Design Thinking into the design process helps generate clearly defined goals and innovative concepts using relevant, user-based evidence.

At Gresham Smith, our visioning process within the practice of healthcare comprises four steps: Problem Finding, Idea Finding, Idea Evaluation, and finally Idea Implementation.

Defining the “Wicked Problem”

Problem Finding begins at the project kickoff. This is where the design team and the client work together to better understand the overarching vision for the project and determine the problem that needs to be solved. This is often referred to in Design Thinking as the “wicked problem.” In other words, a highly complex issue with many unknown factors.

Problem-Finding sessions include the co-design team with anywhere from 12 to 80 people broken into small groups. Participants engage in creative problem-solving activities that typically last between 30 to 60 minutes, with everyone sharing findings with the entire group after each activity.

By design, the multifaceted co-design setup enables transparent communication throughout the process, which is integral to efficient problem solving.

Although COVID-19 threw the world a curveball, our Healthcare design teams have met the associated challenges head-on, successfully conducting Design Thinking sessions online with virtual tools, maintaining flexibility and effectiveness.

How Might We?

Within the Problem-Finding phase, we develop a “How-Might-We?” statement. This is essentially the same thing as the all-important research question and establishes key design drivers that frame the entire visioning process. Design drivers are the foundation for what our Healthcare design teams focus on throughout the project.

For a Flagler Health project in St. Augustine, Florida, for example, we asked: “How might we design a women-centric campus that is centered around wellness, advances the physical, social and economic health of the community, and provides best-in-class care at great value?”

How-Might-We statements are always unique to the client. They might come directly from their vision statement or a Request for Proposal. They can even come directly from conversations that we’ve had with the client.

Problem Finding also takes place during the process design phase of a project, in which nurses, administrators and physicians might map out a typical day-in-the-life, highlighting critical waypoints that represent opportunities for design. This is a great example of using Design Thinking as a research method in a highly engaging way.

Rose, Bud or Thorn?

Where Problem Finding involves asking the client questions about their values, how they work and what they need, Idea Finding allows us to brainstorm as a team and begin to ideate possible solutions.

This is the step in which we engage “super users”—aka departmental champions ranging from a registered nurse who works the night shift to a tech who’s running the floor in a med/surg department. Our goal is for these super users to give us feedback throughout the entire visioning process for continuity.

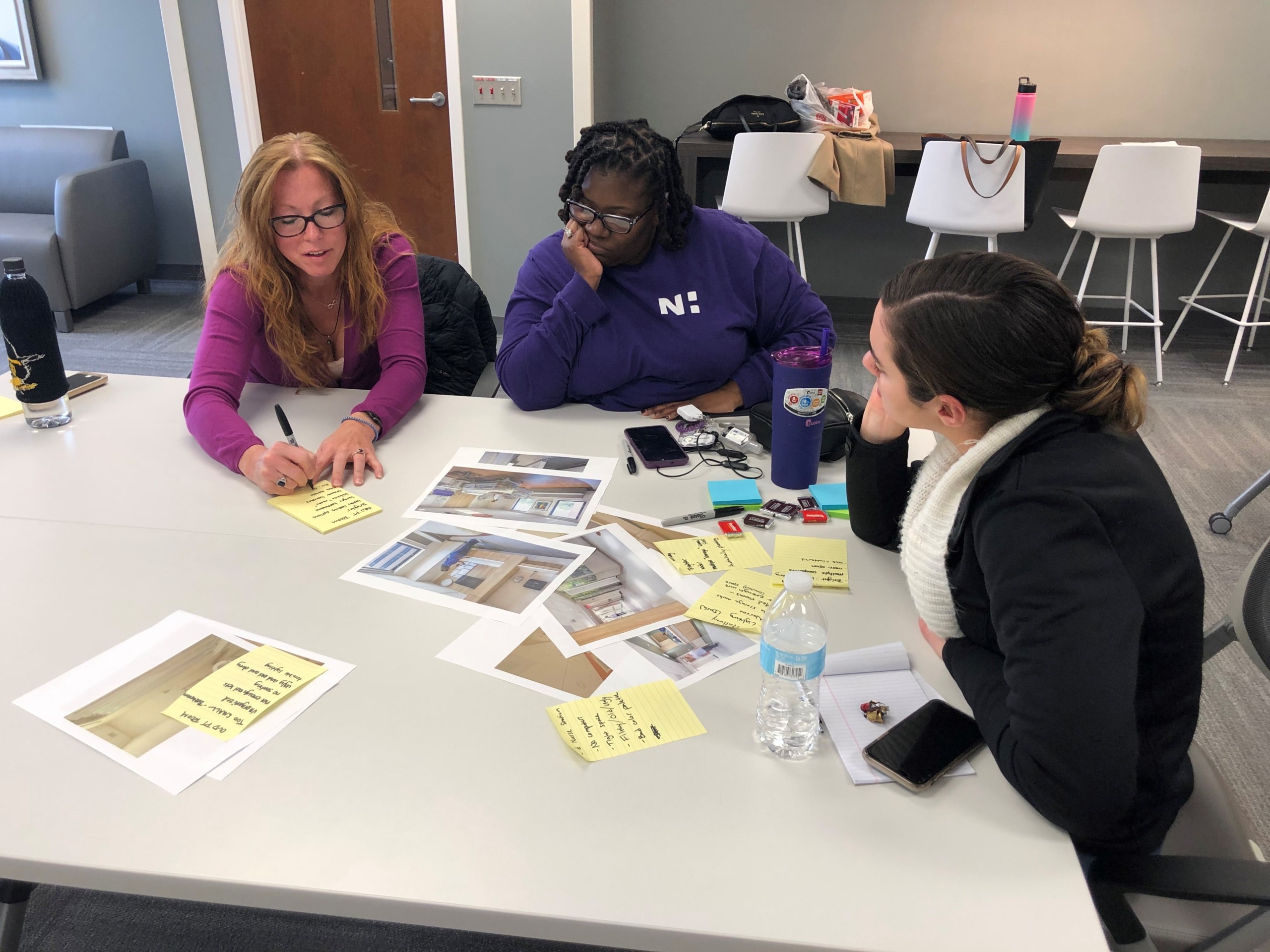

Idea Finding aligns with both the programming and goal-setting phases of a project. In a visioning session for Novant Health during the programming phase, for instance, we set up block plans in a conference room and engaged in a Design Thinking exercise called Rose, Bud, Thorn.

This activity allowed staff to provide feedback in the form of color-coded Post-it notes. Pink, a rose, represented a fantastic idea. Green, a bud, meant the idea had merit but wasn’t quite there yet. Blue, a thorn, signified a bad idea. In this case, the thorn was a departmental adjacency that simply didn’t work.

Measuring KPI

During the goal-setting pre-design phase, we ask for feedback that relates to six key design drivers we apply to every healthcare project: Adaptability & Resiliency; Integration of Technology; Quality & Efficiency; The Human Experience; Healthy, Sustainable Buildings; and Patient Safety.

Each client has key performance indicators (KPI) uniquely important to their organization. These KPI are used to measure the success of a healthcare system—from reducing patient falls to improving the patient experience.

During Idea Finding, we ask the client how they measure those performance indicators and how we might improve them through the built environment. For example, if increased staff satisfaction is a key performance indicator, we might incorporate evidence-based design findings to design areas for staff respite and compare turnover rates from pre- to post-occupancy to measure improvements.

We find this Design Thinking exercise really gets to the heart of what is important to a client and unique to each organization.

The beauty of drilling down into a project through multiple activities is that it gives you a representative sample of an entire organization in about four hours as opposed to three days, which is a standard time frame for a more typical architectural process. It’s a great way to hit the ground running that feeds directly into the design of the project.

Informed by Research: This Is What We Heard

Idea Evaluation takes place during the planning and deliverables pre-design phases of a project. This step is where we analyze the user-focused data and share the findings through Executive Summary reports that give a detailed explanation of the data gathered and every Design Thinking activity that has taken place.

In essence, it’s our way of saying to the planning team: “This is what we heard. Are we on the right track? Did we miss anything?”

It also helps maintain transparent communication and mitigate any confusion from inevitable staff turnover. In the time between early visioning and planning and the actual ribbon-cutting of the hospital, a few years may have transpired. The Executive Summary reports keep the co-design team on the same page.

It’s important to note that during Idea Evaluation, we also work directly with the design teams, who at this stage are going deeper into the project and developing block plans that explain the intricacies of each department. It’s at this point we provide them with literature reviews and visual summaries that help inform what they’re providing to the client.

Powerful, Practical & Customizable

Idea Implementation is the final step in the Design Thinking process. This is where we’ve summarized the findings from the previous step, gathered feedback, and are now making changes.

This is also the stage where we share our findings with key decision-makers, such as physicians and hospital leadership, and gather meaningful feedback post-occupancy on what worked well and what could be improved. This allows our teams to continue to improve their designs and our service to our clients.

Ultimately, Design Thinking is not only a powerful and practical research method but also a customizable tool that design teams can reuse, revise and make their own.

By incorporating it into the overall healthcare design process through the act of creative problem-solving, design professionals stand to gain a greater understanding of some of the issues that can impede both healthcare delivery and healthcare environments and then take the steps needed to help mitigate those challenges.