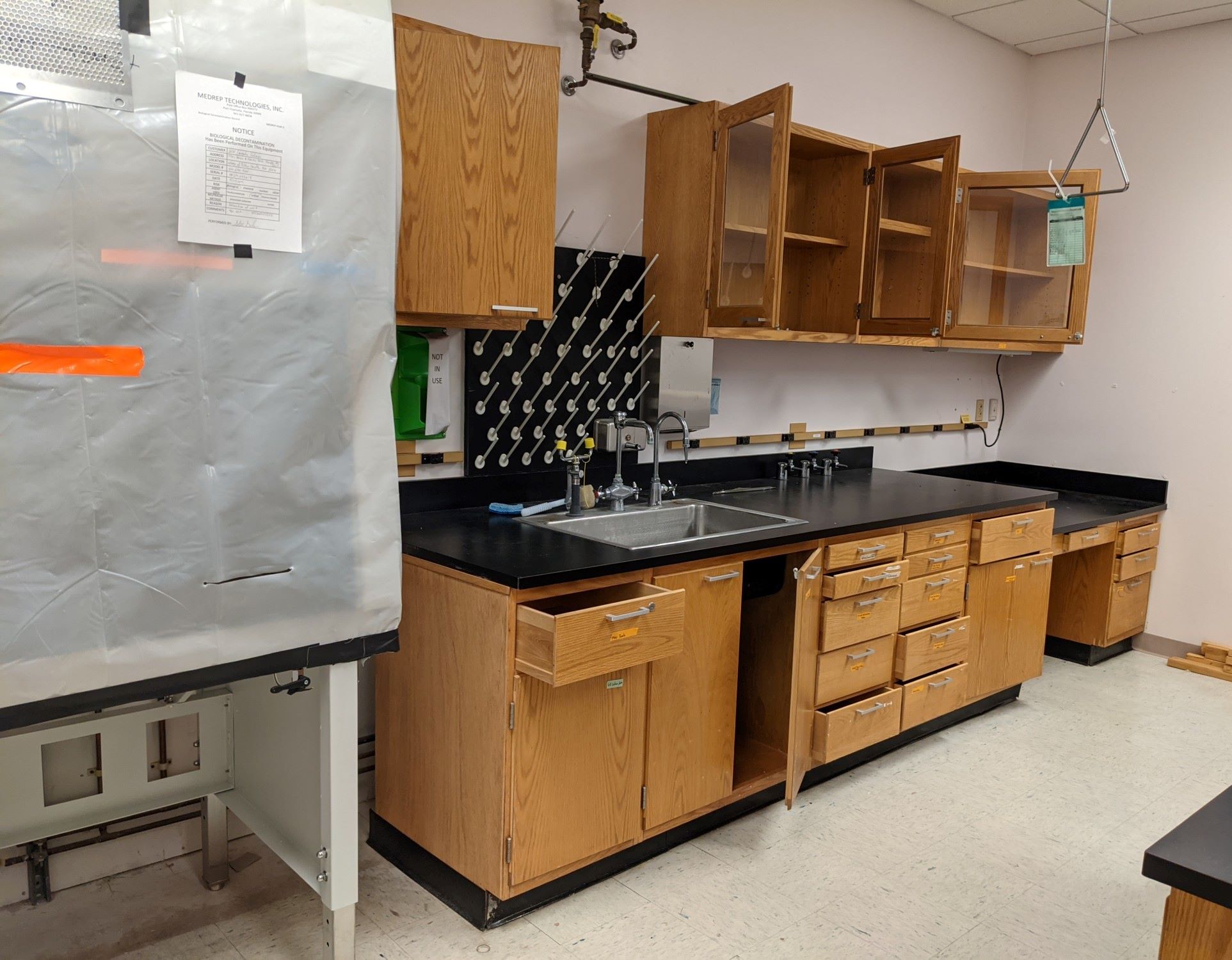

Vinyl floor tiles shine under the glare of flickering fluorescent lights. Dense wood cabinets line the walls of a square, windowless laboratory. A small office sits off to the corner. These are the hallmarks of a circa 1960s to early 1980s research space housed in a vintage campus building. Originally organized around a researcher and their office space, these legacy labs present some unique challenges, especially when it comes to mechanical systems. Think: two different rooftop air-handling systems serving the same space—one for proper air exchanges/exhausting in the lab; one for the office component.

Now, imagine nine stories of those older-style labs stacked and overlapped. The end result is a building program that resembles the game of Jenga® when you map the mechanical systems across the volume of the building. This is a major challenge facing university facilities planning and design departments across the country.

While working with a long-term university client to find space on campus to support a specific type of research, the common theme of inadequate infrastructure to support research space in their older buildings began to emerge in our numerous feasibility studies.

In this blog, we explore how some forward-thinking can help reimagine these existing lab spaces and achieve the transformational change desired by both the client and the end-users.

Master Plan at a Building Level

One way to avoid a Jenga-type building in the future is to plan for older buildings to potentially serve different purposes other than the original design intent. Over time, codes change, and so do research trends and approaches. Therefore, vintage buildings designed for highly specific purposes are less flexible in terms of research space. However, it’s important to note that administrative and office spaces don’t place the same burden on building systems and can be adapted into these existing spaces more easily.

The following are some creative ways to approach master planning at a building level:

- Take a master plan approach to office space. Consolidate administrative spaces into one location to free up space for larger, more flexilble labs. Labs will often need to flex over time depending on demand or grant requirements.

- Understand the client’s overall investment in the vintage campus buildings. Future upgrades can be planned to capitalize on the resources that have already been spent while minimizing disruption to recently updated spaces and building utilities.

- Commission feasibility studies to understand the life span of building systems as well as the upgrades required to meet both immediate and future needs.

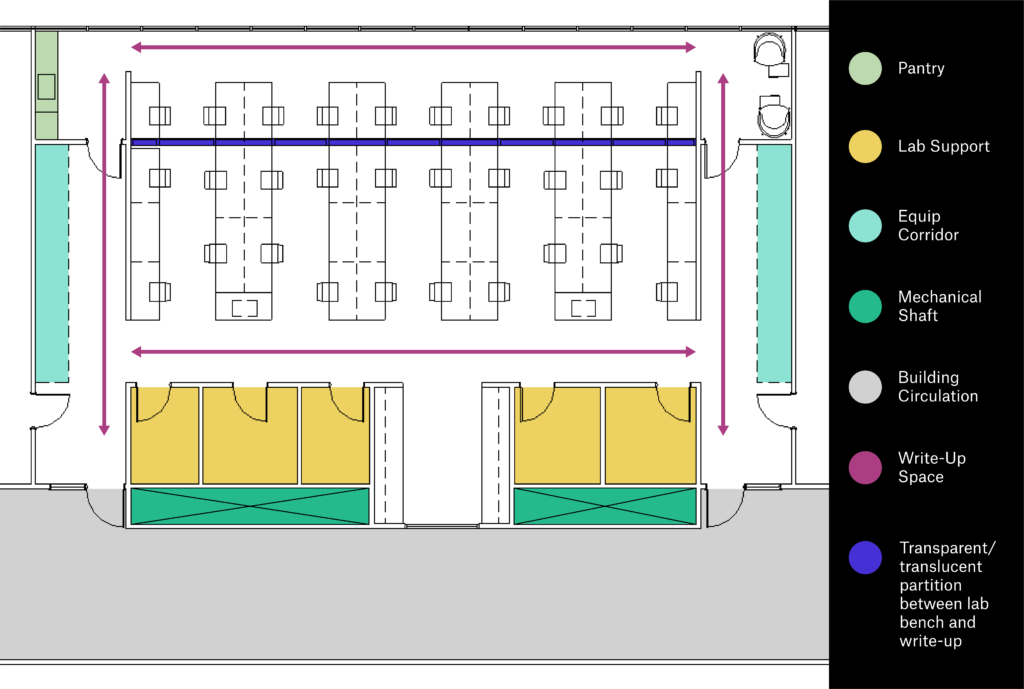

- Allow for separate write-up spaces (controlled spaces adjacent to wet research labs) where researchers can leave their belongings and food before entering a lab. The plan below demonstrates how you can allow food and drinks directly adjacent to the lab bench while keeping visibility high:

- Conduct a review of the building system’s original design versus current codes, e.g., assess mechanical systems and exhaust for research spaces.

- Create interstitial space in the two floors above the lab so you can service all the mechanical units from inside the building. This helps prolong the life of the building by potentially eliminating shaft space depending on how the construction is phased.

- Look at circulation through the lens of end-user well-being. For example, expanding labs to the perimeter of the building not only allows for natural light but also moves circulation inboard.

- Consider visual acuity to the outside from central points for visibility, orientation and safety.

- Add amenity spaces that provide a better space for researchers and promote the sharing of ideas.

- As food is central to interconnectivity, consider building in an amenity space where people can come together over food outside of the clinical research space.

Prevention Is Better Than Cure

We recommend our clients invest in routine preventative maintenance with these older institutional buildings rather than only addressing emergency issues whenever they arise. The old adage: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” is not applicable to preserving assets.

Regularly scheduled active maintenance, which minimizes the chance of failure and costly down time, is a far better approach than responding with reactive maintenance to address failure. Oftentimes, institutions don’t do this because they’re underfunded. However, if you look at the cost for reactive maintenance versus preventative or routine maintenance, it’s far less. So, get ahead of that vicious cycle!

“Regularly scheduled active maintenance is a far better approach than responding with reactive maintenance to address failure.”

The Importance of Phasing

A major challenge for campus institutions is planning for the renovation of an occupied building. Therefore, we recommend phasing the renovation work so it has the least impact on surrounding areas. Our approach to phasing a renovation includes:

- Renovating shared support services first. By separating administrative spaces from lab spaces, these spaces can become a shared resource that remains intact while renovations to lab space are sequenced in future phases as dictated by demand.

- Consolidating core facilities and freeing up swing space. Perhaps new exterior shafts can be considered, or integration of interstitial mechanical space can be created by converting a floor to support building infrastructure to allow for efficient floor plans.

- Sequencing renovations to start on lower floors so that shaft penetrations don’t interfere with future renovations. This protects investments so that renovated spaces remain intact and functional while other phases of work occur in the future.

Promises, Promises!

If you think that addressing aging infrastructure to support campus research labs stops at getting rid of two floors and putting mechanical systems above—think again! There are multiple layers to deal with—from presidents of medical schools and deans of departments to all the things promised in a grant to a potential researcher in order to recruit them.

These promises may have evolved around a specific grant, which could have a five-year life span or even a 10-year commitment. In other words, it’s important to understand that these types of renovations go along with having to deliver on a promise.

Future flexibility down the road is also a major consideration. And when planning for short- and long-term needs, adaptability is critical to support short-term immediate needs as well as longer-term functionality. Additionally, overhead services and utilities, mobile casework, and adopting standard module planning metrics all support a nimble approach to the research environment.

“Understand the client’s overall investment in vintage campus buildings.”

You Don’t Have To Tear It Down

While older campus buildings may appear to be obsolete to the average person, they hold considerable value on the campuses they serve. Ultimately, it’s often more economical and sustainable to invest in renovations and mechanical system upgrades that preserve assets than to invest in a brand-new build.

So, what’s the bottom line? You don’t have to tear down that old campus building to create a new research lab. Sometimes it’s just a matter of reimagining a space and a little out-of-the-box thinking.