Last Spring I wrote a blog post exploring my role as a landscape architect in a profession and system that has resulted in inequalities in our communities. I highlighted the amount of unknown, unrecognized and purposefully erased and/or altered Black cultural landscapes in our country and explored how landscape architects and urban planners can use Black history to not only express a site’s unique attributes, but to also build inclusive and equitable communities. While uncomfortable, my internal examination was necessary for my growth as a person and professional—if we don’t acknowledge our role in furthering systemic issues, we won’t be able to alter our processes and approach to achieve the inclusive and equitable outcomes we say we want.

In this follow-up post, I’m exploring how our landscape architecture studio is challenging ourselves to be a positive disruption—to shine a light on systemic issues and work diligently to chart a different course. By working to understand the community shaping forces at play and making these community connections, we can design better outcomes that address root cause issues and create more inclusive communities. Keep reading to learn how we’re working to honor Black history in various landscapes in Kentucky.

The 9th Street Underpass – Louisville, KY

Collaborators: Tiffany Carbonneau and Susanna Crum

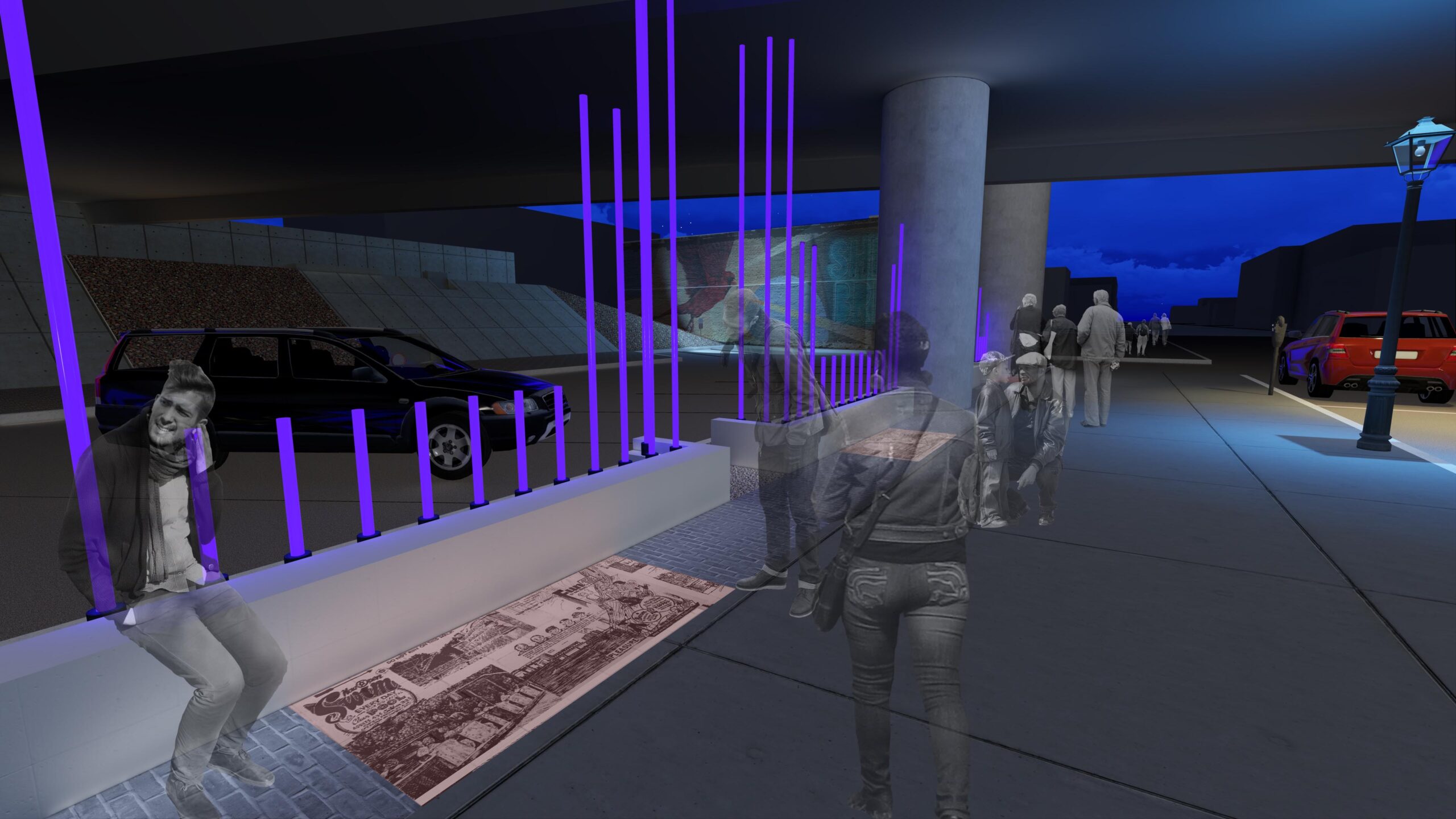

In 2016, Gresham Smith was short listed in a design competition hosted by Louisville Metro Government to develop a concept to strengthen the pedestrian linkage along Main Street under the Ninth Street overpass and transform the space with a short-term public art installation. Ninth Street is a perfect example of how urban renewal was used as a tactic to segregate Louisville, and our multidisciplinary project team’s approach was rooted in researching the history and social injustice of this site, with the goal of transforming a point of division into a point of connection.

Led by local artists Tiffany Carbonneau and Susanna Crum, who focus on the intersection of urban spaces and the powers and policies that shaped them, we found historic photos, post cards and maps that told the story of the destruction that took place at this site during urban renewal. To bring awareness to these issues and allow passersby to engage with the rich Black and civil rights history in Louisville, we proposed framing the intimidating pedestrian space with lighting and seat walls that represented the rhythm and scale of the historic buildings that were demolished. We also incorporated subtle details in the paving to tell the site’s story and highlight important Civil Rights leaders, such as 9th Street’s name sake Roy Wilkins, Ann Braden and Louis Coleman Jr., and cultural landscapes, such as iconic organizing spot Quinn Chapel.

While our team ultimately wasn’t selected for the installation, we learned valuable lessons throughout the design process, like the importance of deeply understanding a site and looking beyond simple physical challenges to identify ways to both acknowledge past injustice while creating new space for inclusion.

Second Street Corridor – Danville, KY

Collaborators: Boyle County Danville African American Historical Society, North Carolina A&T, Jennifer Kirchner, Danville Boyle County Convention and Visitors Bureau

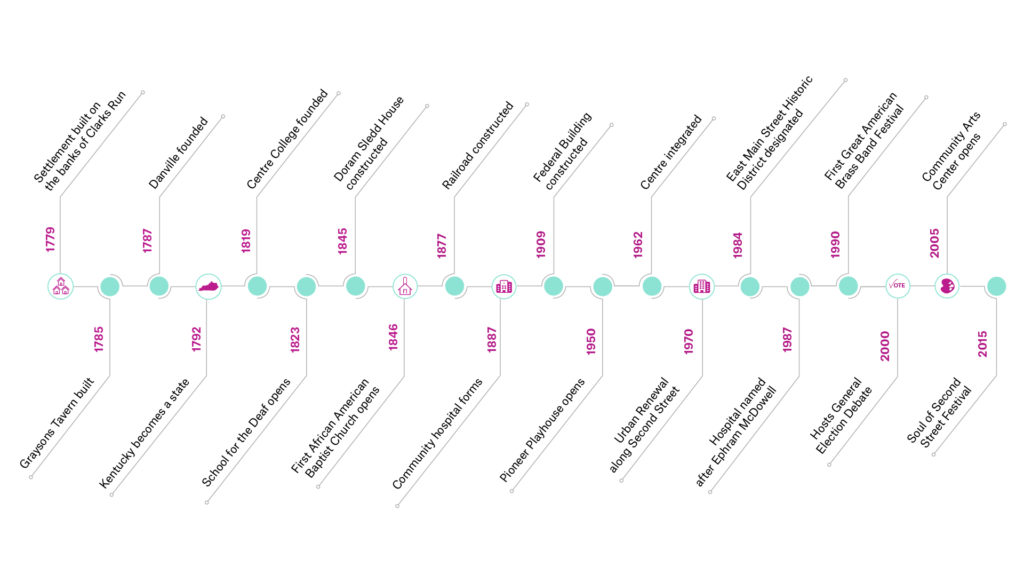

Our studio completed a new downtown master plan for Danville, Kentucky, a small city that lost much of its energy over time due to slowed growth as well as development moving to the metropolitan edges. To help recapture the town’s unique spirit and energy, we worked with Joseph & Joseph + Bravura Architects to co-lead an eight-month planning process, speaking with hundreds of residents, students, business owners and institutional leaders, to identify opportunities for improving Danville’s future.

During our research, we learned that the Second Street corridor and Constitution Square served as the center of Danville’s Black community prior to urban renewal. We connected with Michael Hughes, president of the Danville Boyle County African-American Historical Society, and the conversations with Mr. Hughes and his team, along with the research they graciously shared, more fully contextualized the incremental devastation Second Street corridor experienced and its lasting impact.

Mr. Hughes described Second Street as home to the Black community’s restaurants, social clubs and businesses prior to integration—a vibrant place where Black Americans felt safe and connected to their friends, neighbors and town. However, when you step foot on Second Street or Constitution Square today, this history is omitted from the landscape.

Since Danville is a small city, Second Street was not included in the original scope of the downtown master plan. However, our team took this opportunity to go beyond the project scope and, as Dr. Bohannon describes it, “decenter our design practices” to tell a more complete and inclusive story. Since Gresham Smith had recently committed to a Diversity by Design Partnership with North Carolina A&T State University—the only Historically Black College and University in the country with a landscape architecture program—we pitched this project to Professor William “Chris” Harrison as a way to begin building a relationship with their students.

Throughout the fall semester of 2020, NCA&T’s undergraduate landscape architecture students developed a series of concepts for how to express and interpret these stories in the landscape. After a series of studio sessions and many great ideas explored, we landed on one student concept, developed by Silas Lindsey, that created a series of connected, self-guided tours that tell a rich story of African American history in Danville.

Once their semester completed, our team built on much of what the students and Silas had developed and developed a concept titled “ReAnimate.” The concept proposed developing augmented reality applications to showcase Mr. Hughes’ and the Danville Boyle County African-American Historical Society’s photographic research and pop-up kiosks with auditory and additional visual elements to re-establish the vibrant experience that once existed on Second Street. This proposal could be implemented incrementally to build awareness and momentum for the project, making it possible to tell these stories of Danville’s African American history without expensive, permanent physical infrastructure. The ReAnimate concept has since has been more formally integrated into the Downtown Masterplan, and our team and enthusiastic community partners are continuing to investigate short- and long-term ways build a more inclusive narrative about the City’s history and people.

Splash! at Charles Young Park – Lexington, KY

Collaborators: Fluidity, Joseph & Joseph + Bravura Architects, EHI Consultants, Shrout Tate Wilson MEP.

Last summer, Lexington-Fayette County Urban Government engaged our team to design “Splash!,” a new water play feature, outdoor classroom and public gathering space at Charles Young Park in Lexington, Kentucky’s historically Black East End neighborhood. The City had previously installed a temporary solution called “SplashJam,” which was a huge hit and made it clear that any improvements to this park needed to be for and of the community. The goal of this new park feature is to complement the recently completed playground while also connecting the community to the newly constructed Town Branch Commons greenway. Throughout the design process, our team is embracing a South African slogan from Maurice Cox’s essay A Tale of the Landscape: “Nothing about us, without us, is for us.”

“Nothing about us, without us, is for us.”

Named after a decorated soldier, teacher, diplomat and civil rights leader from Kentucky, the Charles Young Park and Community Center was dedicated on March 3, 1935 and was a vital addition to the East End at the time. Throughout its 85+ year history, the center and park have continued to act as essential public infrastructure for the local community. Excerpts from the Lexington Herald-Leader in 1940 describe business and professional group meetings and city-wide table tennis tournaments hosted at the community center, and as recently as this year the community center provided critical access to vaccinations to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

As designers, our job is to make sure the new park feature lives up to Colonel Charles Young’s name and prioritizes the East End’s people and culture. Since beginning the design process, we’ve hosted discussions and workshops with stakeholders at the community center and gained incredible feedback that informed the physical design of the water play feature, walkways and safety features. We’re also collaborating with community force Yvonne Giles, who is helping collect and coordinate community-sourced stories that will be permanently integrated into the play space. Ms. Giles is also helping the City and Parks Department lay the groundwork for adding additional story telling moments over time. Splash! is slated to break ground in 2022 and we cannot wait to experience the results.

The Work Continues

These are simply three examples of how Gresham Smith is acknowledging and integrating Black History into our work. We still have much to learn about the systemic issues that have shaped our communities and there are many ways we can continue to improve our practice. As we learn and grow, we are building more equitable and inclusive design processes each step of the way, which will result in more equitable and inclusive design outcomes. As we all know, nothing good comes easy, but when you invest your time and efforts in people, it’s always worth it.