National Hispanic Heritage Month runs from September 15 through October 15. It’s a time to reflect on and celebrate the histories, cultures and contributions of American citizens who can trace their roots to Spanish-speaking countries, such as Spain, Mexico and certain parts of Latin America, including the Caribbean. The celebration begins in the middle of September to coincide with national independence days in several Latin American countries, including Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Costa Rico, Mexico and Chile.

To celebrate this year’s National Hispanic Heritage Month, we sat down with Christina Florez, a senior engineer in Gresham Smith’s TSM&O group and a member of the firm’s IMAGE (Inclusive Multiculturalism for Advancement, Growth and Equity) Employee Resource Network, to discuss her Hispanic heritage. Along the way, she shared the story of her Cuban mother’s journey to the U.S. and gave us a lesson about the difference between Latino and Hispanic.

Have you ever experienced any misconceptions about your Hispanic heritage?

Christina Florez: Throughout my life, I’ve personally experienced a lot of: “You can’t be one of them because you don’t look like one of them. You don’t sound like one of them.” And my response is always the same—we come in all shapes and sizes as well as colors, from the whitest white to the darkest dark. There’s no one feature that defines us all. We’re from all over the map, and not just from the Caribbean or Central or South America. We’re also European because of our Spanish origins.

Both my maternal and my paternal great-grandparents were Spaniards who came from the northern part of Spain. So, I was born with blonde hair, blue eyes and fair skin. My grandparents and parents were born in Cuba, and I was born in Puerto Rico and raised stateside. So, I’m an American—which brings up another common misconception. Many Americans don’t realize that Puerto Ricans are fellow citizens. And that may have something to do with the fact that Puerto Rico isn’t a state. Instead, it’s a U.S. territory. This means that, even though Puerto Ricans don’t vote in presidential elections, they are United States citizens.

Can you help us understand the difference between Latino and Hispanic?

Christina: While Latino and Hispanic are sometimes used interchangeably, they have different meanings. I’ve noticed that even within the Hispanic community, there’s not a clear understanding of what the difference is between the two.

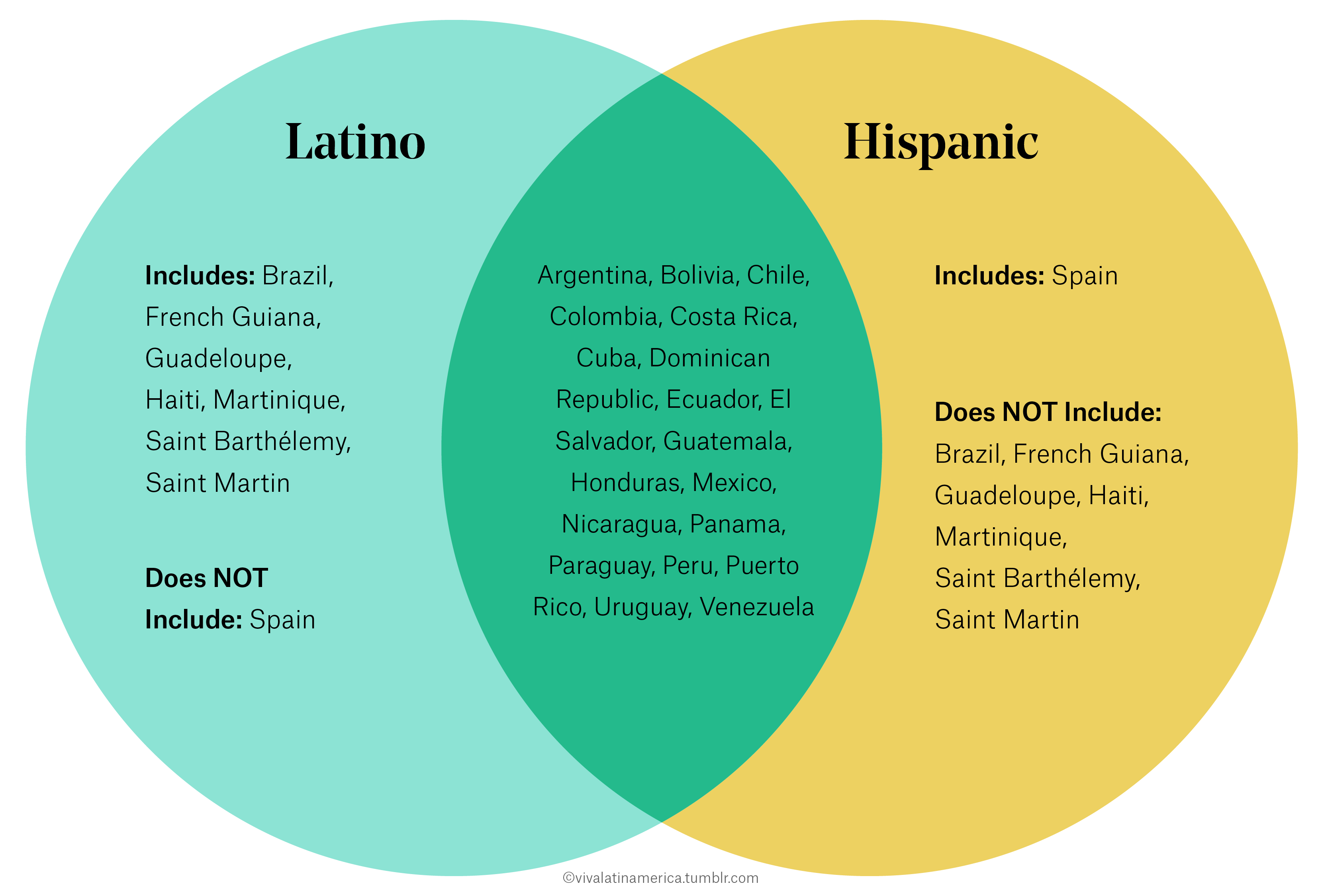

Hispanic traditionally refers to Spanish-speaking countries. However, not all Latino people speak Spanish. Therefore, people who are Hispanic may vary in their race and also where they live or originate. For example, a person from Mexico or a person from Venezuela might both call themselves Hispanic [as evidenced in the intersection of the Venn diagram above] because they share a spoken language and a legacy of Spanish countries. Hispanic does not include countries like Brazil or Guiana as they typically speak French and Portuguese.

Conversely, Latino refers to geography—specifically, people of Latin American origin, including Central America, South America and the Caribbean [as seen in the overlap of the Venn diagram]. Like being Hispanic, being Latino says nothing about your race, as Latinos may be white, Black, indigenous, Asian and so on. Latino does not include Spain, and comprises non-Spanish-speaking countries like Brazil, Guiana and Haiti.

What does your Hispanic heritage mean to you?

Christina: My Hispanic heritage is a definitive part of my core being. I’m proud of it and I’m proud of my family. When my mother was 11 years old, her father was shot by one of Fidel Castro’s revolutionaries, and she was one of over 14,000 unaccompanied Cuban minors who were airlifted from Cuba to Miami in the early 1960s as a part of Operation Pedro Pan. The airlift program was an agreement between the U.S. State Department and the Miami Catholic Diocese.

The children were sent stateside because of fears that Castro and the Communist party were planning to terminate parental rights and place minors in communist indoctrination centers. It’s a story that’s not often told or taught in schools, but the operation represented the largest mass exodus of minor refugees in the Western Hemisphere at the time. And it’s 100 percent why my family is here in the United States.

When the children arrived in the U.S., most of them already had family members here who they could live with while waiting for their parents to arrive from Cuba. However, many children didn’t have any family stateside, so they had to stay in orphanages run by the Catholic Church. From there, they were placed with foster families in Miami and throughout the country.

In my mother’s case, she was put on a plane without any of her family members and ended up in Puerto Rico where she was reunited with her sister. They were then sent to New York. After a while, they eventually made it back to Puerto Rico, where they met up with other family members who had traveled there.

I can only imagine how much courage it took for my mother to endure that experience. The fact that she not only survived but thrived after that is amazing. If you ask me: Who are your heroes? My answer is my mother and my family.

What overarching message would you like to get across to others during National Hispanic Heritage Month?

Christina: That it’s not only important to tell stories about our heritage but also to listen to them. We don’t want to forget our history or to dismiss it. It’s what makes our country great, right? Unless you’re an indigenous American, we’re all originally from somewhere else. And our backgrounds are all so eclectic and different. We need to celebrate and embrace that diversity. Hispanic Heritage Month gives us an opportunity to do that.

“My Hispanic heritage is a definitive part of my core being.”

Just because, do you have any favorite foods or music as they relate to your Hispanic heritage?

Christina: My favorite traditional Cuban comfort food is roasted pork and sweet plantains. We traditionally make our pork on what we call a Caja China. Essentially, it’s a Cuban-style pig roast that involves a roasting box with an aluminum tray inside. You skewer your pork—aka your pig—place it inside the tray, cover it with a metal tray that’s topped with hot coals, and then slow roast it for hours.

The end result is the most tender and juicy pork you’ll ever eat. I personally don’t eat the skin, but some people will fight tooth and nail for it! We eat it at Christmas. We eat it on New Year’s. We eat it at Easter. It essentially defines the holiday season for my Cuban family.

As for the Cuban sweet plantains known as maduros, they’re made with very ripe plantains, which are like bananas, only larger and tougher, that are fried in oil until they’re crispy and caramelized. And they’re a perfect side dish to the roasted pork. When it comes to music, my workout playlist is mostly Spanish because it’s vibrant, it’s lively, and it gets me moving!